Expanding on "Mental Cartography:The Map Is Not The Territory that I published, I discussed how philosophers use the phrase “The map is not the territory” to highlight the gap between our mental representations of the world vs the reality we live in. We use maps—metaphors, models, theories—to help us navigate life, but they remain simplified reflections of the terrain they represent. From a Buddhist perspective, the mental ‘map’ idea is closely aligned with Buddhism concepts. So here is a quick Zen perspective on all this—because Buddhism has an older, and equally-interesting, take on "The map is not the territory”.

In Buddhism's own version of General Semantics, every Buddhist tradition has “The map is not the territory” expressed. Buddhism explores concepts, labels, and habitual patterns of thinking so that any seeker or Buddhist can also identify this and other mental frameworks. And Buddhism did this a couple thousand years before Western Philosophy existed. In the same way we remind ourselves that a map is not the actual landscape it depicts, Buddhist practice teaches us to look beyond the illusions and fixed ideas that keep us distanced from the genuine nature of experience.

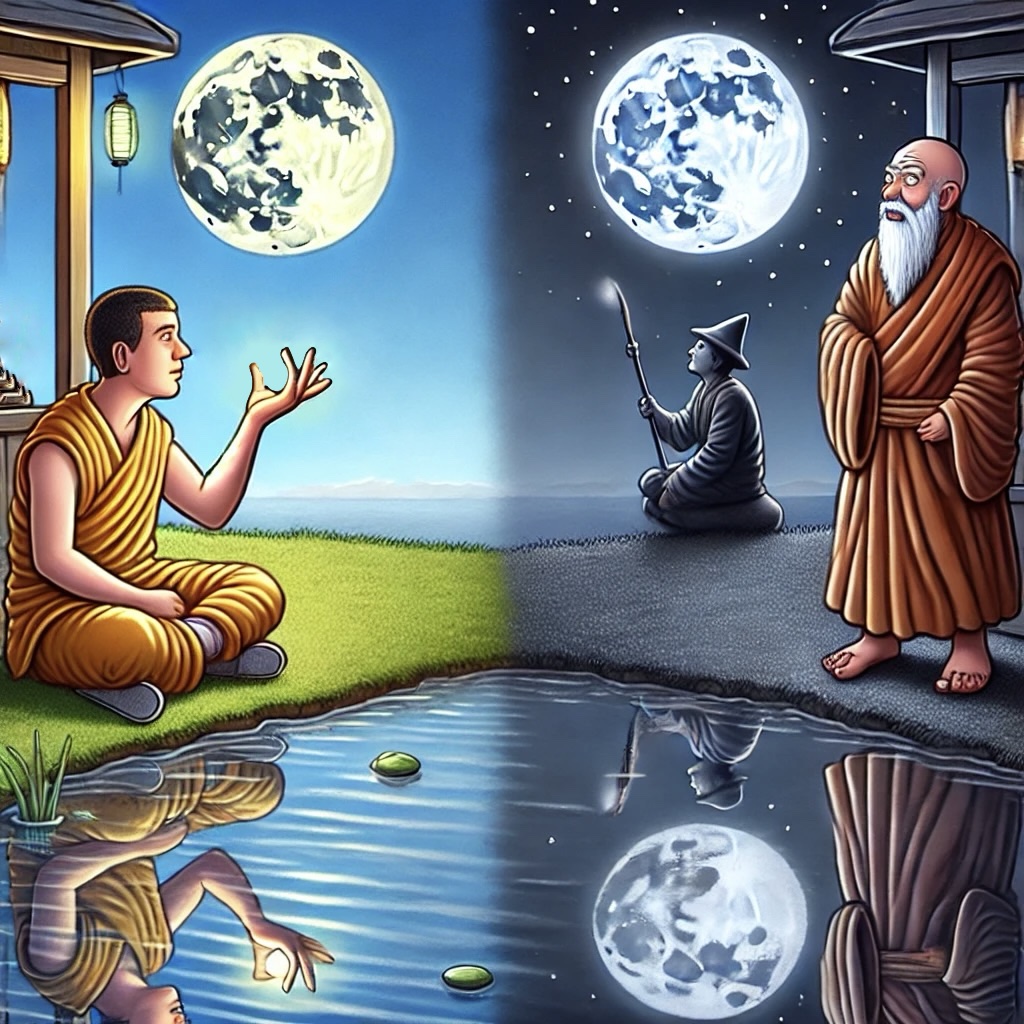

Buddhist principles and concepts like upaya (skillful means), sunyata (emptiness), and direct experience come into play with Buddhism's own version of “The map is not the territory”. While that saying may come from Western thought, the parallels in Buddhism are striking. In fact, we often see an echo of this principle in Zen teachings: “The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon.”

In Buddhism, our minds apply labels and concepts to everything we encounter: we call things “chair,” “tree,” or “person,” and subconsciously attach all sorts of ideas and expectations to those labels. This tendency to label is not inherently wrong—it’s practically necessary to name and navigate our environment. However, it can also become a trap when we confuse the label (map) for the actual object or phenomenon (territory).

A classic Buddhist teaching says we create a “conceptual overlay” atop our experiences. We cling to these overlays, believing our mental constructs are the reality. This is the foundational meaning of the phrase “the map is not the territory” in a Buddhist sense. Just as a map can be incomplete or even outdated, our concepts can reflect only partial truths or illusions. We see and interpret what our conditioned minds want to see.

Emptiness (Sunyata)

The idea of sunyata, often translated as “emptiness,” underscores that any phenomenon we encounter is empty of a permanent, fixed essence. From a Buddhist perspective, this emptiness signals that all things are interdependent and in flux. “The map is not the territory” also suggests something similar: the territory itself is deeper, more dynamic, and too nuanced to be captured in a flat or static framework.

So labeling a situation (or a person) with a few concepts doesn’t reveal that situation’s infinite network of causes, conditions, and influences—its true nature. A map can be extremely helpful, but Buddhism says, "let us not confuse it with the living, breathing complexity of the land." Buddhism has a concept called the ‘two truths,’: a distinction between relative "truth" (or conventional truth, or our "map") and absolute truth (the world as it is).

Skillful Means (Upaya) and Mental Maps

In a practical sense, maps exist to guide us. We rely on them to choose paths, set goals, or find vantage points. In Buddhism, similarly, teachings (sutras, commentaries, practices) are like maps designed to lead practitioners toward enlightenment—or at least to reduce suffering. A person new to mindfulness might rely heavily on meditation instructions to cultivate present-moment awareness. Those instructions, while essential, are still just a “map”—a method—pointing to the direct experience that arises during meditation.

Buddhism also uses the idea of upaya, or “skillful means,” to describe the different techniques and teachings that help people approach awakening. Upaya is the recognition that there is no singular, "one-size-fits-all" map for all beings. Instead, the best ‘map’ to use is the one that speaks to the individual’s current mindset and life situation. Even so, skillful means are never the final reality; they are practical strategies for discovering or unveiling truth.

Letting Go of Attachment to Directly-Experience The "Territory"

A notable pitfall in using mental models ("maps") is attachment. We grow so comfortable with a particular map or technique that we cling to it, and our Ego wants to always be right. This can create dogmatic thinking: “My map is better than yours,” or “This is the only correct path.” In Buddhism, clinging—even to something labeled ‘spiritual’ or ‘sacred’—can obstruct our ability to see the real, actual world clearly.

In Zen stories, teachers sometimes appear to contradict earlier lessons, not because they lack internal consistency, but because they point out that students have mistaken the map for the territory. By pulling away the student’s reliance on a single viewpoint, they provoke the insight that reality has no single vantage point to fixate upon.

Buddhism wants you to, if you can (not all can, or want to), directly-experience the "Territory". Zen Buddhism captures this nicely with the saying, “The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon.” The gesture (the map) shows where to look, but ultimately you must look at the moon (the territory) yourself! If you spend all your energy analyzing the finger—its shape, its appearance, or its direction—you’ll miss the *direct experience of the moon’s light in the sky.

Many Buddhist schools place tremendous emphasis on direct experience. Meditation is not an intellectual exercise; it is a lived, felt, continuous awareness of the present. Our mental commentary about “this is good” or “this is bad” is the map. The textures, sensations, and nowness of the present moment, of direct experience—be it sound, breath, or emotional states—are the territory. Going back to the Western version of “The map is not the territory”, "touching the grass" of the terrain and experiencing the landscape (looking hard at "what is objectively so") can sometimes be assumptions we challenge in figuring out "what's real*"—meditation is all about this, and other things.

In practical terms, mindfulness is the practice of remembering that our thoughts, labels, and judgments are fleeting and partial. During meditation, we may become aware of a feeling, such as anger, and automatically attach an entire storyline about what caused it, who’s to blame, and how to fix it. When we meditate, we can pause at that moment of anger and just observe the underlying sensation. The mindful pause keeps us anchored in the territory (of objective reality, or "what is so) rather than lost in the map of mental chatter.

The Takeaway

When we take Alfred Korzybski’s phrase—“The map is not the territory”—and view it through the prism of Buddhism, we see that it resonates profoundly with fundamental Buddhist teachings. Through mindfulness, meditation, and the various upaya that the traditions offer, practitioners learn to question their habitual perceptions. They discover that the world is richer, more nuanced, and more alive than any label or conceptual framework can capture.

In this sense, Buddhist practice is less about discarding maps and more about using them wisely. Each concept, ritual, or teaching can be a point of reference—an arrow pointing us to the “moon” of direct experience. Ultimately, however, the deep joy and freedom come from letting those maps fall away when necessary and meeting each moment in its raw, unfiltered reality. Buddhists say we shouldn't deny the value of a good chart, but we should never mistake it for the ground beneath our feet!

By remembering that the map—even a cherished spiritual or wonderful map—is just not always the complete territory, we free ourselves to explore life with fresh eyes and an open heart. And in doing so, we walk a path of discovery that Buddhists and many Western Philosophers all believe leads to genuine insight and liberation.

Happy Seeking and Learning!

“Rely not on the teacher/person, but on the teaching. Rely not on the words of the teaching, but on the spirit of the words. Rely not on theory, but on experience. Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. Do not believe anything because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything because it is written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and the benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it.”

The Buddha, Kalama Sutta