Alfred Korzybski’s “The map is not the territory” comes from his work in General Semantics (and 1933 book Science and Sanity). At its core, the phrase "The map is not the territory" means that our mental representations (maps) of "reality" are not the same as the “actual territory" of reality itself. We use these “maps”—language, concepts, beliefs—to navigate our world. But maps are still only abstractions, simplified models that leave out infinite details. This principle has parallels in other philosophies dealing with “how things occur” for us, how we form our views, or any perception that is distinct from objective reality.

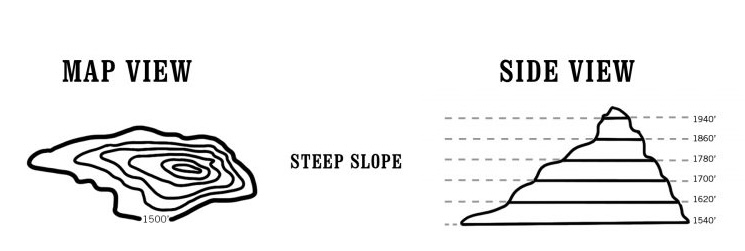

When we describe something in words, or think about anything conceptually, we create an abstraction—akin to a map charting the terrain. No matter how detailed that map (of "reality" in our heads), it is still not the actual physical ground itself:

Other frameworks deal with the above concept as well. For example, Buddhism has a concept called the ‘two truths,’: a distinction between relative "truth" (or conventional truth, or our "map") and absolute truth (the world as it is).

The philosophical framework of General Semantics teaches that language is generative: it doesn’t just describe events; it also shapes how we perceive and interact with those events. Because of this, it’s crucial to remain aware that our words and concepts are always simplifying something that is probably more complex (or unknown to us).

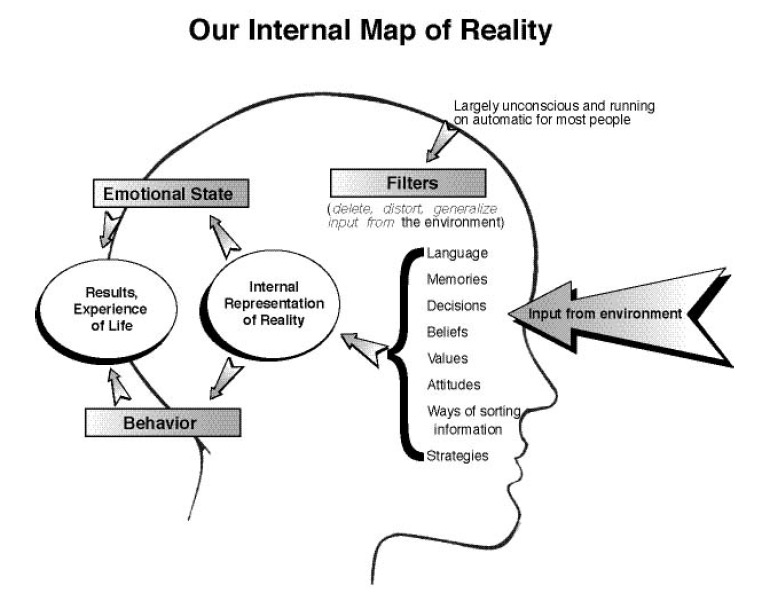

We all understand, fundamentally, that reality (the territory) exists outside of our minds (and our maps). But we never stop to look at how we build our mental models. We take in input from our senses, from language (conversation, reading), and from social sources—then we automatically formulate our mental models and create our maps—we experience the world this way. Here's a chart I created to illustrate “The map is not the territory”:

We rely on maps every day to manage complexity or simplify things: newspapers, bank statements, or maybe your HR policy manual. Maps are there to distill complexity, and give you some indication of the lay of the land (who things are). But do things like a financial statement of a company, which boils down the complexity of thousands of transactions, really tell you anything about what’s going on inside the company...or if their products or services are any good? To accept that we all have mental models, or "maps", means to also understand that they will always be missing details about the "territory" they cover.

Reality is inherently complicated, and messy—which explains our desire to simplify it. It’s what we’ve always done as thinkers, religious scholars, and explorers to name a few cartographers. However, if the goal shifts from comprehension to simplification, we often confirm our views with other "cartographers'" maps. Certain mapmakers (influencers, tv personalities, etc), share their maps to push their take on the territory—media mapmakers especially! You just want to take care when you see claims by others of "how it is", especially if they're paid to encourage you to update your own map with theirs. We are always around people trying to influence our views and merge their map. If we're not sure about our own interpretations and understandings about the territory, it's tempting to "get a new map"—but caution: we can easily forget that our own mental model (map) is, ultimately, a simplification and cannot cover all aspects of the "territory" ("what is so", reality). There are a lot of great resources we use to adjust our own maps—but if we're not careful we can mistake the map for the territory. We could begin making poor decisions on unexamined map data—and the GPS could drive us off a cliff!

Wait a minute—this isn’t really about maps at all, is it?

This is about thinking (mental models) and staying open-minded to new information about "the territory" (objective reality outside of our own head)! Relying solely on maps (our mental model—and our interpretations etc) can lead us the incorrect conclusions, better to go “touch grass” now and then: explore the territory as a reality-check. To explore the territory is to verify your map and challenge your assumptions. The territory experienced is better than the territory believed! What do I mean by this?

If all you're doing is reading the "map", the territory (reality) can crash into you and coldly trash your "map"! Maps and models are not meant to be static references for eternity; they are meant to be more dynamic tools, and our mental models should be used for exploration and testing our assumptions too...just as much as we use them for understanding and navigating the territory.

To use our maps or models as accurately as possible, we should consider three crucial principles:

- Consider the cartographer’s perspective (and motivations, sometimes).

- Reality is THE the best update to any map.

- Maps (mental models) can shape territories (reality) for us—and we need to learn that sometimes can have it the other way around.

Ego is a cruel master, and we like to think that our perceptions always align with reality: “what is”. I am sorry to report that most of us really love to feel we are correct. 😂 We forget that our map (mental model) is only a representation, we risk dogmatism: holding onto certain “truths” as if they are the reality. We might dismiss nuances, reject new raw data: Fear and Ego like to shoot down anything that contradicts our internal maps. When we fail to recognize that other people operate with their own “maps” (interpretations, mental models, etc), things can get a little intense. Remembering that our map might not match the territory reduces misunderstandings, judgment, and helps you keep an open mind.

As human beings with powerful minds and language, we should understand that we can never experience “pure territory”—we're always experiencing the map. Our task is learning to notice when we’re mistaking our mental model as being absolute truth—and stay open to revising our mental maps! Other "cartographers" vie for our attention (news anchors, thought leaders, politicians etc) and we can conflate another's map data with our own (and reality itself), thus distorting actual territory. Some people may be good mapmakers, just be wary of anyone saying their map gives you actual objective reality—the raw data of the territory: nobody can do that, but you yourself! As I said before: The territory experienced is better than the territory believed*!

The Takeaway

“The map is not the territory” reminds us that our mental models of the world we live in (and experience) are rarely (read: never) the same thing as: the actual world itself. Our perceptions often can differ from reality, and it’s automatic that we won’t always notice this. That is why this concept even exists: our conceptual frameworks are not identical to actual reality (objectively what is so — in reality).

This perception/reality mismatch is normal, natural, and can be harmless. For example: we can dine on cognitive bias our whole lives, and never be unhappy in the world we live—and most people do. But when we’re trying to achieve a goal or seize a new opportunity—it isn’t very safe to misunderstand the map—for the actual territory.

Revising our maps can be a challenge at first, because it involves reconciling our preferred assumptions with what genuinely (and objectively) exists in the territory.

Throughout our lives we depend on maps from authorities, commentators, and educators. Still other people will offer us their maps, as well. In these situations, the best course of action is to choose our mapmakers wisely—seeking those who are candid, rigorous, and open-minded and are willing to adapt. Those are the best mapmakers.

The ability to use this map/territory distinction encourages us to see the world as it is, not as we interpret or imagine it. So we want to be prepared to adjust our mental maps every so often. And when choosing map data by other cartographers, just be intentional and choose wisely.